Essay: Remembering the slave trade yesterday and today

And the misery goes on

The slave trade was an atrocity that shaped the modern world. Without Britain the commercial trade in human beings could never have become such a vast and profitable trans-national industry. Written to mark the 200th anniversary of the trade’s abolition, the following essay by Mark Cantrell pointed out that a modern version of slavery is alive and well and unlikely to be abolished anytime soon

|

| Am I Not A Man And A Brother? |

Imagine the scene, as a disgruntled Wilberforce is

barged aside by Tony Blair desperate for any legacy but a 19th

Century equivalent of the Iraq War; perceive his finery and mad grinning visage

as he proclaims: “We have not so much abolished slavery as modernised it. Er…”

Then wait for the titters, as the audience realise

that in his love of ‘modernity’ Blair has caught himself in a tangled web of

his own conceit, while the freed slaves accept the minimum wage and Gordon

Brown’s sleight of hand tax ‘cut’ through gritted teeth. Of course, after the

brutalities of total slavery, the transition to wage slavery must seem like

freedom indeed. But that’s by the by.

Abolition

TODAY, 25 March 2007 [as it was when this essay was first published], the UK

celebrates the bi-centenary of the abolition of the slave trade. It brought to

an end what had hitherto been a major and profitable British commercial

venture. Fortunes were made for a few, misery and death for the many, and the

consequences of this hideous business linger to this day.

Racism was born of slavery. So, it gained a new lease

of life as the Imperial project took off in the Nineteenth Century with the

orgy of colonial land-grabbing, but it was born in the blood and savagery of

the slave trade. It was manufactured to justify the trade and the institution,

to excuse the brutal treatment, the torture, rape and murder of human beings.

While the practitioners may not have thought it through quite so rationally,

the academic CLR James put it succinctly in his book The Black Jacobins. In answer to the question, why would traders tolerate

so much destruction of their valuable wares, he answered: because clearly and

inescapably their captives were human beings – not beasts – and so they had to

be broken, abused, physically and psychologically ground into the dirt. It was

a brutal and brutalising business.

As a slaver’s manual noted at the time: “Terror must

operate to keep them in subjection.”

Conservative estimates say that between 10 and 15

million people were shipped across the Atlantic. Other figures put it as high

as 30 million people. Casualty figures amongst the captives are put at around

five per cent in prisons and as much as ten per cent once the voyage commenced.

As we know of the conditions aboard ship, they were packed into the hold as

tight as proverbial sardines. They were kept like that for months, little

exercise, little food, with brutal reprisals for disobedience or even the

merest hint of rebellion. Sometimes, slaves were killed simply as a warning to

the others – who might have been forced to eat a slice of the hapless victim’s

organs.

Slaves did rebel of course. Even shipboard, they

sometimes managed to slip their shackles and overpower the crews. The film Amistad took its story from one such

group of slaves who managed to seize control of the ship carrying them, though

it focused on the idealistic reformers who fought for their freedom in the

pre-Civil War US courts. It’s telling in two senses, this film, the first in

that slaves could and did overpower their oppressors, and in the second that

their own actions in the slow, painful death of slavery tends to be airbrushed

out of the scene.

On the whole, we who live in the nations that

invested in – and profited from – the trans-Atlantic slave trade, find our

focus directed towards the white, generally affluent, individuals who

campaigned for the end of the trade. As in Amistad,

and as in the new released film Amazing Grace, black figures are rendered the recipients of white justice and

idealism, with a few token noble and dignified – but otherwise somewhat passive

– black faces to play a supporting role.

“Material being produced today to mark the

anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade makes it appear that white

people liberated black – the assumption being that they could not do it

themselves,” Ken Livingstone wrote recently in the Guardian newspaper. “In reality, slaves rose against the trade from

its inception. This broke it… No one denigrates William Wilberforce, but it was

black resistance and economic development that destroyed slavery, not white

philanthropy.”

The first recorded slave revolt took place in 1570.

In the centuries of the slave trade’s existence, there were over 200 shipboard

rebellions. In the Caribbean islands, a brutal and violent society flourished

as the slave owners found themselves surrounded inevitably by hundreds of

thousands, millions, of enslaved people. Outnumbered, the reign of the day was

terror and brutality – but it never stopped revolts and even protracted

episodes of guerrilla war as the slaves resisted.

In the wake of the French Revolution, in 1791, when

the ideals of the rights of man were lighting fires of idealism across the

world, the colony of St Domingue erupted in revolt. At its head was an

illiterate slave named Toussaint L’Ouverture. He and his self-liberated slaves

went on to defeat the British and the French militaries – two of the most powerful armed forces in

their day – sent to put down the revolt. The only successful slave revolt in

history founded the first independent black republic of Haiti. Alas, what

military might failed to achieve, in time global economics brought it back

under the fold of dominant European-spawned powers.

Toussaint was fired by the ideals of the French

Revolution and the Enlightenment (at least those parts of Enlightenment

thinking that hadn’t declared him to be a sub-species). He was a believer, and

believed that men of reason could talk through their differences, and to that

end he travelled to Paris in the hope of negotiating a settlement with

Napoleon.

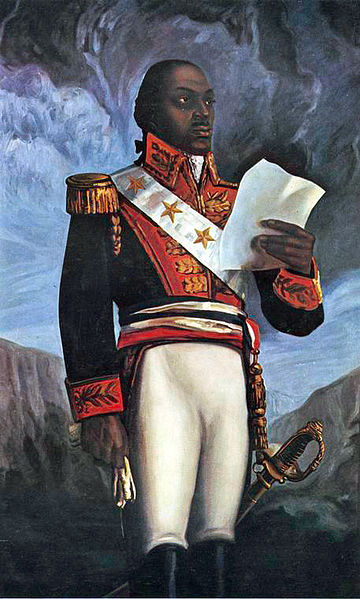

|

| Toussaint Louverture |

The British arm of the slave trade continued, for a

few brief years, until its abolition in 1807, yet slavery itself wasn’t

abolished in British controlled territory until 1833, and of course it lingered

longer in the United States until the Civil War finally put paid to it.

Slavery’s last stand.

In Britain’s northern industrial cities, the

denizens of the ‘dark satanic mills’ also played their part in the wider

context of slavery’s demise. As the industrial revolution continued its

breakneck conquest of human life, subjecting more and more to its rigours and

the poverty of market-defined subsistence wages, these workers, these wage

slaves, were making connections between their own plight and the plight of the

slaves. These men and women perceived a sense of solidarity, as they faced their

own brutal punishments for resisting the rising wealth of the captains of

industry. Bitter strikes and disputes wracked the urban landscape in Britain.

Proto-unions were forming, and often, former slaves and anti-slavery

campaigners would find a willing audience among these rough and degraded people

who worked the new capitalism of industry.

As the century passed from that 1807 abolition of

the trade, many British workers continued their sense of solidarity with their

enslaved ‘brothers’ and ‘sisters’ across the Atlantic. As the Civil War in

America raged, the loss of cotton for the mills led to unemployment and

hardship for Manchester mill workers, but even so, many supported the war

against the Confederacy and its proclaimed aim of ridding slavery for good.

Such solidarity, while it might in practice have had

an often contradictory expression, and while the individuals themselves might

have been tainted by the racist legacy of the trade, nevertheless played a

significant part in the groundswell of opinion that drove slavery to its death.

The struggles of slaves to achieve

self-emancipation, coupled with the rise of early working class militancy,

religious and moral outrage, and the rise of a new industrial mode of wealth

creation, all conspired against the slavers. The trade had its roots in the

earliest phase of capitalism, but capitalism as an economic system has no sense

of sentimentality or tradition – it eats it own and it helped to destroy what

it first helped to birth. In a sense, however, slavery had done its job: it

helped to shape the birth of the modern world. By the time the trade ended, the

blood of millions of people had bought and paid for the West’s rise to global

domination.

Alas, the story of slavery doesn’t end there.

Modernisation

TODAY, on the 25 March 2007 [as was when first published], two centuries after the

formal abolition of the slave trade, it is worth pointing out that slavery

exists in the context of wider economic forces. It doesn’t float in some

abstract sea of abuse – and since a slave is a source of labour then it fits

into the spectrum of the exploitation of labour.

As in 1807, so too in 2007, slavery persists.

Whereas it once operated in the full light of day,

with those in the trade – at least in the upper echelons – perceived as

‘respectable’ businessmen, it now operates in the shadows of criminality.

Economic conditions still play their part, however, for what is a slave but the

attempt to obtain and control the cheapest extraction of value from human

labour? It remains profitable enough to survive, even if it clings only to the

niches and fringes of the mainstream economy.

The trade is nothing like its trans-Atlantic

predecessor, of course, but the forms that slavery takes today breed no less

misery for the victims. So, in the run up to the bi-centenary, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) published ‘Modern Slavery In The UK’, a report into the prevalence of slavery today. It was

carried out by a joint team from the University of Hull and Anti-Slavery International. It shows that slavery is alive and well in the UK, particularly

as a result of people trafficking, and makes the valid point that the problems

exist within an international context that will inevitably make difficult

strategies to combat the modern slavers.

“All forms share elements of the exploitative

relationships which have historically constituted slavery,” the JRF said when

launching the report. “[These are] severe economic exploitation, the lack of a

human rights framework, and one person’s control of another through the

prospect or reality of violence. Slavery is defined and prohibited under

international law. Coercion distinguishes slavery from poor working

conditions.”

The latter is surely a moot point; when is coercion

not coercion? Of course, we take it to mean direct physical or psychological

compulsion to force someone to work for very little or no pay at all. However,

in conditions of abject poverty, if someone faces the ‘free’ choice of

gruelling toil rather than begging or starvation, is that not a form of indirect

coercion?

It’s a question that can distract from the focus on

slavery, from the point of view expressed in the report. Inevitably, given its

remit, it is the more direct coercion and ‘theft of liberty’ that forms a

slave. Otherwise, there is a danger of losing the focus in the myriad forms of

social problems faced by people today.

Having said that however, it raises the important

point about the context of slavery. It exists in a spectrum of labour

relations. If slavery represents the dark and brutal pole of ‘employment’, then

the other pole is work as we know it. The kind where we take a job with a going

rate, enjoy statutory protections and rights, have the ability to leave that

job without fear of reprisal, or indeed withhold our labour in a time of

dispute with our employer. Between these two poles is the global context of

child labour, sweatshops, economic migrants as they are called, and so on.

Slavery exists in a place where so many factors and

issues overlap, forever in danger of falling through the cracks and gaps where

overlaps fail to quite mesh. While being an important human rights issue, it is

also a matter of workers’ rights. An attack on the rights and protections of

one worker is an attack on them all – and let’s face it, the slave is the

weakest and most exploited of all labour. For workers, no matter what they

enjoy, it is an important issue for the preservation of the wider employment

protections. And, in an echo of old, the shipment – or trafficking to give its

modern term – across national borders brings in the sphere of immigration

policy.

These days, so many countries have little regard for

the majority of immigrants; they are a source of fear and loathing and cheap

macho politics that it creates a useful smokescreen to mask the trafficker.

According to Anti-Slavery International, there are

some 12 million people in slavery across the world. While the International

Labour Organisation says that 2.4 million people are enslaved by people

traffickers, forced to work for the gangs who smuggle them, often in the sex

trade. Not every slave is trafficked by clandestine gangs smuggling them over

borders. Some arrive in a country quite legally, but then are violated into the

abusive world of slavery, their passports and documents withheld and threatened

with violence to themselves or their family members.

Some UK companies, knowingly or otherwise, are

relying on people working in slavery to produce the goods they sell, the

organisation said. A complex web of sub-contracting and supply chains, managed

by agents elsewhere, masks the slavery: a murky screen blinding us to the

existence of the abused slave in our midst.

The JRF added: “Slavery in contemporary Britain

cannot be seen in isolation. Most of those working as slaves in the UK have come

from elsewhere, often legally. This makes slavery an international issue. Many

relationships of enslavement trap people by withdrawing their passports or ID

documents, making escape unlikely. Evidence shows that those who protest about

the appalling working conditions may be beaten, abused, raped, deported or even

killed.”

Furthermore, trafficked people are often subjected

to forced labour through a mix of enforced debt, as well as intimidation. For

those who might escape the clutches of their captors, they also run the risk of

finding the UK authorities unsympathetic – perceiving them as illegal

immigrants rather than victims. Often, not only is the victim unaware of any

rights they may have, so too are the authorities who might subsequently end up dealing

with the victim.

Part of the problem in the UK’s approach to tackling

trafficking, according to the JRF, is the Government’s view of it as an issue

of migration control. In other words, the ever-shifting goalposts on

immigration, and the endless changes and confusions bred to keep people out,

are assisting the traffickers to control their wares. There is little in the

way of joined-up protection for those who fall victim to the slavers.

In part, this is no doubt because our vision of

slavery is shaped by the understanding of its classic form abolished two

centuries ago, but mainly the hugely negative paranoia and anti-immigrant

feeling whipped up by successive generations of politicians out for a cheap

headline.

It leaves the vulnerable even more exposed.

“Current protection and support services for

trafficked men, women and children are inadequate and there is no specific

assistance available to those who are trafficked for labour exploitation,” said

Professor Robert Craig. He is one of the report’s co-authors and the Associate

Director of the Wilberforce Institute for the Study of Slavery and Emancipation

at the University of Hull.

He added: “A review of the position of most

organisations active in this field suggests that formal adoption by the UK

Government of the various treaties and conventions in place would be an

important first step.”

Frankly, given New Labour’s record on the

immigration issue, such as the use of deprivation and poverty as a failed attempt to force asylum seekers

out of the country, it is unlikely the Government will take any serious steps

to combat the modern scourge of slavery.

Government ministers like to boast of their

progressive record, yet as headlines in other topics show, it is becoming

ever-more strident in its authoritarianism. In New Labour’s time in Government

the gap between rich and poor has widened. Yet the Government likes to boast of

the numbers it has raised from poverty, even though such numbers are still

swamped by levels of deprivation. It boasts of the minimum wage it introduced,

raised recently by a most generous 17 pence an hour, even while the cost of

living has steadily risen. To this, add Gordon Brown’s flourish as he – hopes –

to graciously accept the keys to No 10: his final Budget. The generous tax cut

for the lowest earners, commentators and analysts agree, is anything but.

Gordon gives with one hand and takes with the other,

it was said. As with the Budget, so it can be with rights and protections

granted to vulnerable sections of the workforce.

Spurred on by cases of abuse experienced by migrant

workers who came to this country to work as cooks, cleaners and nannies, the

Government introduced legal protections in 1998. They arrived in the country

legally to work in their employer’s home. In some cases, they also lived there.

Some fell victim to sexual abuse, physical assault and sometimes were kept as

an effective prisoner by their employer. Not so much domestic workers, as

domestic house slaves.

Under the legislation, they are legally entitled to

leave their employer for another job if they are abused and receive basic

protection, and also to receive the minimum wage under UK employment law. It

was seen as a positive move to end what for some workers had become ‘virtual

slavery’.

Some 17,000 such migrant workers come to the UK

every year, but now they face losing the protections they gained courtesy of a

Home Office plan to introduce new immigration rules, which will drastically

curtail their rights. The plan means that such workers can only enter the

country on non-renewable business visa and are barred from finding another job

if they leave their employer’s service because of mistreatment. The intention

is to stop ‘abuse’ of border controls, the Home Office claims.

A Home Office spokesman told the Independent newspaper: “These are not

migrant workers but people who are ordinarily employed and resident outside the

UK, so changing employers in the UK would not be appropriate. As part of our

continued work to combat trafficking, our emphasis will be upon delivering

robust pre-entry procedures, including appropriate safeguards, such as the

identification of cases of possible abuse at the pre-entry stage to minimise

the risk of subsequent exploitation.”

Quite how such bureaucratic procedures can combat

the commercial shipping and trading of human beings is quite another matter. As

far as campaigners who work with victims of such abuse, it will do nothing to

help those who are smuggled in for the sex trade or as illegal workers in other

trades, merely leave this group of migrant workers isolated and defenceless.

Unless, of course, they wish to present themselves to the authorities and be

processed as some kind of criminal. Or, indeed, accept their status as slave.

Naturally, the Government has been accused of

hypocrisy.

A lack of joined up thinking, or the result of

deliberate policy? The police, of course, deal with the situation on the

ground: the actual cases of abuse. The immigration service deals with caseloads

and the bureaucratic implementation of policy from ‘on high’. And for all the

tabloids foam at the mouth over the issue of the Government’s ‘softness’, this

is not an immigrant-friendly government.

On the anniversary of the classic slave trade’s

abolition, it might be something for the Government to commit to some drastic

and far-reaching endeavour to abolish the modern trade. At least something

positive to help the victims who manage to slip their shackles, but for all its

vocalised commitment to combat trafficking, it is more than likely that

Government deed will contradict Government proclamation. Spin and

self-aggrandisement as ever comes before substance.

They can’t even apologise for Britain’s role in the

slave trade, it happened so long ago, yet they’ll take a share of the glory of

its two-century-old abolition. An apology would cost them nothing, show

character, acknowledge that the trade was a terrible crime against humanity.

The city of Liverpool was heavily involved in the trade, and in 1999 the

council showed the strength of character to formally apologise for its past

role. The Church of England Synod followed suit.

In his article in the Guardian, Ken Livingstone, London’s elected Mayor, took the

opportunity to apologise for London’s role in profiting from the trade. He

called upon the Government to do the same.

“The British Government’s refusal of such an apology

is squalid,” he added. “Until recently, almost unbelievably, it refused even to

recognise the slave trade as a crime against humanity on the grounds that it

was legal at the time… Slavery was the mass murder of millions of people.

Germany apologised for the Holocaust. We must for the slave trade.”

One is

tempted to suggest don’t hold your breath. Tony Blair, looking to leave No 10

and the ‘ingratitude’ of the nation behind, is seeking to secure his legacy and

move on. Doubtless, after gaining the legacy of Iraq, and trying desperately to

leave it behind, apologising for the British State’s involvement in an atrocity

abolished 200 years ago is perhaps a little too close to the bone. Slavery both

new and old is someone else’s problem now.

When it comes to ending the modern trade in human

beings, as with the end of the classic slave trade, it is a mistake to expect

the ‘great and the good’ to eradicate the scourge and emancipate the victims.

While a few sincere and dedicated individuals will take a stand and campaign,

putting a public face on the wider grass roots opposition, it is the latter

rattling and shaking the chains that will truly end the abomination of slavery.

As before, it will be a long hard, thankless struggle.

As for

New Labour, no Government of Wilberforces is this; expect them to take the

credit and bask in the second-hand glow of glory, but don’t expect any action.

This essay was written for, and first appeared on, one of the author's earlier blogs and appeared circa April 2007.

Leave a Comment